It feels quite fitting that Joachim Trier’s “Louder Than Bombs” features voiceover narration comes from all different characters. The writer/director frequently harbors novelistic ambitions in his work, and this feels like a stab at the ambitious multi-tongued narrations of Faulkner. Yet in trying to swing for the fences, Trier really just demonstrates how thin a grasp he has on the differences between literature and cinema.

Granted, this device is partly excused by the fact that the story has no real protagonist. Because “Louder Than Bombs” is a story about loss, it’s somewhat fitting that the center of the film is a departed character. The narrative is one of absence, not about presence. Such a choice comes with a cost, however. Trier’s film feels largely empty. Where one would normally find a heart, there is little more than stale air.

As the family of acclaimed war photographer Isabelle Reed (Isabelle Huppert) picks up the shards left by her sudden departure, Trier seems to consciously avoid the clichés of similar movies. The widowed father (Gabriel Byrne) resists becoming emotionally absent; the eldest son (Jesse Eisenberg) remains cooly distant; the younger son (Devin Druid) feigns normalcy. Yet avoiding banality does not guarantee quality. It is not enough to merely remove the bad if it is not replaced with something else good. And Trier has little of substance to offer.

“Louder Than Bombs” plays like the kind of film made by someone who has seen movies and read books about grief but has never really experienced it – or at the very least, has never really come to terms with it. Be it in the performances, the tone or the content, every moment feels motivated by the art being imposed onto the events rather than the emotion that ought to flow from them. People grieve singularly, to be sure, and it is not for anyone to say how it should or should not be done. But Trier’s choice to stand so far outside the messy, complicated reality of mourning and rebuilding provides scant insight into the very thing he seeks to depict. C+ /

There are many stories surrounding cycling icon Lance Armstrong worthy of cinematic treatment. There’s the athlete himself, whose hubris and competitive nature led him to dupe, receive and betray. There’s the many authorities who turned a blind eye, including the media – save the one journalist, David Walsh, with the courage to take on Armstrong’s cabal. And of course, there’s America as a whole, who cheered on his triumphant narrative and marveled aghast when it was exposed as a sham.

There are many stories surrounding cycling icon Lance Armstrong worthy of cinematic treatment. There’s the athlete himself, whose hubris and competitive nature led him to dupe, receive and betray. There’s the many authorities who turned a blind eye, including the media – save the one journalist, David Walsh, with the courage to take on Armstrong’s cabal. And of course, there’s America as a whole, who cheered on his triumphant narrative and marveled aghast when it was exposed as a sham. Really, truly and sincerely – I cannot think of a recent movie that I watched with more dispassion or disinterest than “

Really, truly and sincerely – I cannot think of a recent movie that I watched with more dispassion or disinterest than “

May has arrived, which means the lineup for the Cannes Film Festival is officially out. Each year, the official selection provides an extra impetus for me to catch up with the work of world filmmakers whose previous features might have eluded me. Admittedly, I am still working my way through the lineup from the years I attended the festival. Whoops.

May has arrived, which means the lineup for the Cannes Film Festival is officially out. Each year, the official selection provides an extra impetus for me to catch up with the work of world filmmakers whose previous features might have eluded me. Admittedly, I am still working my way through the lineup from the years I attended the festival. Whoops. Did you like “

Did you like “

Any tweak on the “great man” biopic is welcome, though the pendulum need not swing as far in the other direction as Robert Budreau’s “

Any tweak on the “great man” biopic is welcome, though the pendulum need not swing as far in the other direction as Robert Budreau’s “

The British cinema scene is full of people doing lots of interesting work, but it still gets reduced quite frequently to familiar genres: the black comedy, the kitchen sink melodrama, the suburban crime saga. In his debut feature, “Down Terrace,” Ben Wheatley has the gall to meld all three into one audacious genre-mashing movie. The result is something spry and altogether wonderful, so much so that it is my selection for the “F.I.L.M. of the Week.” (In case you’re just joining this six year old column, that’s a contrived acronym for “First-Class, Independent Little-Known Movie.”)

The British cinema scene is full of people doing lots of interesting work, but it still gets reduced quite frequently to familiar genres: the black comedy, the kitchen sink melodrama, the suburban crime saga. In his debut feature, “Down Terrace,” Ben Wheatley has the gall to meld all three into one audacious genre-mashing movie. The result is something spry and altogether wonderful, so much so that it is my selection for the “F.I.L.M. of the Week.” (In case you’re just joining this six year old column, that’s a contrived acronym for “First-Class, Independent Little-Known Movie.”) Sundance Film Festival

Sundance Film Festival The story of Xavier Giannoli’s “

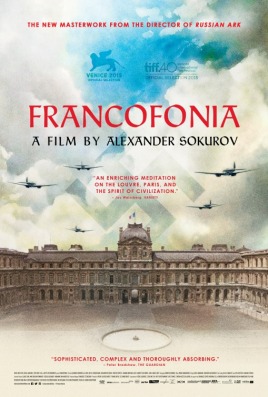

The story of Xavier Giannoli’s “ As the names usually saved for the closing credits roll at the outset of Alexander Sokurov’s “

As the names usually saved for the closing credits roll at the outset of Alexander Sokurov’s “

Recent Comments