Arguably the most famous close-ups in cinema history take place in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” the 1928 silent classic that elevated the expressively tight framed shot of facial contortions to the position of high art. Dreyer later said of the close-up, “Nothing in the world can be compared to the human face. It is a land one can never tire of exploring.”

It’s a blessing Dreyer did not live to see Tate Taylor’s “The Girl on the Train,” a film that puts the close-up to shame through bludgeoning and excessive use. This specific shot is the movie’s only language to convey the internal agony of its three leading female characters. No need to waste time detailing the multitude of other techniques available at Taylor’s disposal, so let’s just leave it at the fact that the close-up is lazy shorthand for emotional intimacy.

The camera tries to substitute the reservoirs of feeling hidden by the icy women, each with their own secrets to bury and axes to grind. Their blank stares into the distance are meant to convey restraint or secrecy; instead, they convey nothing. One only needs to hold up the work of star Emily Blunt in “The Girl on the Train” alongside her performance in “Sicario” to see the difference. In the latter film, the most minuscule movement in Blunt’s face communicates a complex response to the ever-shifting environment around her character Kate Macer. Here, as the alcoholic voyeur Rachel Watson, Blunt is reduced to gasps and gazes that do little to illuminate her psychology.

“Juno” still ranks among the top 10 quoted movies at my house, so it should come as no surprise that the on-screen reunion of that film’s mother-daughter pair (Allison Janney and Ellen Page) in “

“Juno” still ranks among the top 10 quoted movies at my house, so it should come as no surprise that the on-screen reunion of that film’s mother-daughter pair (Allison Janney and Ellen Page) in “

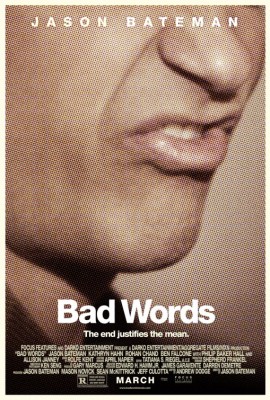

Jason Bateman has long been saddled with the reputation as a go-to guy for playing the uptight, no-nonsense straight man in comedy. After having finally watched “Arrested Development,” I can see why he got typecast – he’s quite skilled at it. But too much of a good thing can get quite boring, and he’s rarely given a great supporting cast to whom he can react.

Jason Bateman has long been saddled with the reputation as a go-to guy for playing the uptight, no-nonsense straight man in comedy. After having finally watched “Arrested Development,” I can see why he got typecast – he’s quite skilled at it. But too much of a good thing can get quite boring, and he’s rarely given a great supporting cast to whom he can react. How ironic that director Lynn Shelton should begin to lose her touch in the film “

How ironic that director Lynn Shelton should begin to lose her touch in the film “ It’s hard to talk about authorial intent in “

It’s hard to talk about authorial intent in “

Recent Comments